Thomas Paine–Revolutionary

He was not born into auspicious circumstances.

He was not born into auspicious circumstances.

Thomas Pain (the ‘e’ at the end of his name would be added on his arrival to America in 1774) was born in Thetford, England in 1736 to an Anglican mother and a Quaker father. His schooling lasted until age 13, when his education ended and his apprenticeship began as a corset-maker, the trade of his father. It would not be a speculation to assume that this life greatly bored Pain, for at age 16, young Thomas escaped Thetford, and made for the east coast of England to join the British Navy. His deployment aboard the British privateer The Terrible, in the command of a certain Captain Death, was scuppered by his Quaker father, Joseph, who arrived at quayside moments before Thomas boarded ship. Effectively talked out of this enterprise by Joseph, young Tom Pain soon found himself back in Theford, immiserated. However, three years after his first attempted escape, Pain did manage to get himself aboard another privateer, King of Prussia. After seeing action against the French in the Seven Years War (or as we North Americans refer to it, the French-Indian War), and fortunate not to have been injured or killed by wood-shattering cannonball or other hazards of sea battle, he was discharged from the King of Prussia with some war-time spoils–naval service being a somewhat piratical enterprise in those days–and plotted his next move.

He inevitably settled in the town of Margate, England. Setting up shop as a corset-maker, this time as his own boss, he married and set out to have a family. But he was soon visited by bad fortune: his business went belly-up, his wife died in pregnancy, and to make matters worse, so too his child. For the next ten years, from 1759 on, he took a position as an excise officer for the crown, but was fired on an accusation that he purposely failed to properly inspect goods. Back to corset-making he went to make ends meet, but he got his job back as excise officer when the judgment against him was vacated. Ambulant again, he eventually landed in the town of Lewes, South Sussex, where he stayed until 1774, just long enough to marry (and separate) from another woman, start (and fail) at another business venture (this time a tobacco shop), and get himself fired from his job as excise officer yet again. (There’s more to the story regarding his second sacking in this position. Ostensibly he was fired for leaving his post. But the real reason was probably due to his first foray into pamphleteering. In 1772, he wrote The Case of the Officers of Excise, which argued for better wages and working conditions for both he and his colleagues. It sold four thousand copies, providing him a tidy profit and some notoriety. But it was a pyrrhic victory, for Pain’s dismissal two years hence was, in all likelihood, due to this broadside aimed at the crown and parliament.) Barely avoiding debtors prison after being brought to his knees financially, Pain made his way to London in 1774. It was there that he reconnected with an admired acquaintance, Benjamin Franklin—they had met several years earlier, and formed a mutual respect—and thus expressed a desire to Franklin to start afresh in the New World. Franklin obliged Pain with a flattering letter of recommendation. Tom Pain was about to become Thomas Paine, and the course of American history, and by extension world history, would be changed forever.

Mr. Paine Goes To America

“The bearer, Mr. Thomas Pain [sic], is very well recommended to me as an ingenious, worthy young man. He goes to Pennsylvania with a view of settling there. I request you to give him your best advice and countenance, as he is quite a stranger there. If you can put him in a way of obtaining employment as a clerk, or an assistant tutor in a school, or assistant surveyor (in all of which I think him very capable) so that he may procure a subsistence at least, till he can make acquaintance and obtain a knowledge of the country, you will do well, and much oblige your affectionate father”–Letter of Recommendation from Benjamin Franklin to his son William Franklin, Governor of New Jersey, regarding Thomas Paine, 1774

Pamphleteering was the equivalent of blogging in the 18th century; anyone with an opinion and access to a printing press could publish and distribute with relative ease. Thomas Paine, landing in Philadelphia in late 1774, found himself in “exactly the right place at the right time”[1]. Throwing himself head-first into the argy-bargy world of “tavern-based discussion groups”[2], he made all the right connections almost immediately. Robert Aitken was one of those connections. A bookstore owner and proprietor of the publication The Pennslyvania Journal, Aitken was on the prowl for talented writers. He asked Paine to join his operation as managing editor; Paine gladly accepted. The quality of his work immediately showed him a natural.

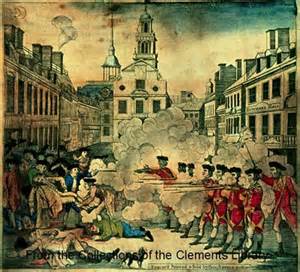

The French & Indian War (1754-1763) had been the catalyst for a great deal of conflict between the crown and the American colonies in the post-war years. Due to the high costs of repulsing the French and protecting American colonial interests, parliament was of the mind that the Americans should pay back the favor–and the debts Britain incurred–in kind. Beginning in 1765, a raft of taxes and other acts fell upon the colonies: the Stamp Act, the Townshend Act, the Quartering Act, the Tea Act. There was not one American MP (member of parliament) to argue on behalf of the colonies in the House of Commons. Devoid of parliamentary representation to redress these grievances, cries of “no taxation without representation!” flew up. The more agitated the colonial populace became, the more heavy-handed British authorities responded. Bloodshed seemed inevitable. In 1770, British soldiers in Boston fired at a rowdy– but unarmed–mob. In what is now known as the Boston Massacre, five colonists lost their lives. On the other end, British excise officers, intent on enforcing these parliamentary acts, were increasingly subjected to cruel acts of reprisal. (Tarring and feathering being the chosen method of inflicting retribution on the King’s excise agents.) In 1775, a full-blown skirmish erupted in the Massachusetts towns of Lexington and Concorde between colonial militias and British troops. Rebellion was in the air.

The problematic relationship with the British was widely discussed and debated, but even after the bloodshed of 1775, talk of independence still took a back-seat to talk of resolution. Enter Thomas Paine. First writing under the nom de plume(s) Atlanticus or Amicus, Paine was under no misgivings as to what he though was the proper course of action: independence. “When I reflect…I hesitate not for a moment to believe that the Almighty will finally separate America from Britain. Call it independence or what you will, if it is the cause of God and humanity, it will go on.”[3] But Paine’s writings for the Journal would come to an end under acrimonious circumstances towards the end of 1775. Yet another reverse for the unfortunate Mr. Paine it seemed, but this time, good fortune lay just around the corner. His dismissal from the Journal allowed him the freedom to write Common Sense.

Common Sense

“Of ‘Commons Sense’ it can be said, without any risk of cliche, that is was a catalyst that altered the course of history.”–Christopher Hitchens

It is alleged that Thomas Paine wrote Common Sense at the behest of his friend, Dr. Benjamin Rush, a lesser-known but prominent “Founding Father”, who was a signer of both the Declaration Of Independence and the United States Constitution. Told by Rush to write a clearly-stated pamphlet in support of the American cause–while instructing him to avoid calling for all-out separation from the mother country–Paine chose to go the opposite route, vehemently calling for a complete decoupling from Great Britain. He was an effective polemicist for the simple reason that he was a self-educated man. As a result, he could communicate an intellectual argument for colonial self-rule in the language of the average, moderately educated reader. He was also a man with quite an ax to grind with the crown, due in no small part to his rough treatment at the hands of the British establishment in retribution for his pamphlet, The Case of the Officers of Excise, years before. So…no half measures for Paine now. On Common Sense, none other than George Washington was later to say that Paine’s tract was instrumental in swaying a huge swath of the American public behind the movement for independence. It was Paine’s phraseology as well–terse, economical, and on-point–that was so very persuasive to the man-on-the street:

“These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.”–The American Crisis, Thomas Paine, December 23rd, 1776

Paine, while giving deference to certain aspects of the unwritten British constitution, went all-out on the two most important aspects of British governance: monarchical rule, and hereditary transfer of governmental authority. He spared no harsh word in describing the absurdity of monarchy and heredity:

- “One of the strongest natural proofs of the folly of hereditary right in kings, is, that nature disapproves it, otherwise, she would not so frequently turn it into ridicule by giving mankind an ass for a lion.” [4]

- “How a race of men came into the world so exalted above the rest, and distinguished like some new species, is worth inquiring into, and whether they are the means of happiness or of misery to mankind.”[5]

- “It is the pride of kings which throws mankind into confusion.”[6]

- “In England a king hath little more to do than to make war and give away places; which in plain terms, is to impoverish the nation and set it together by the ears. A pretty business indeed for a man to be allowed eight hundred thousand sterling a year for, and worshipped into the bargain! Of more worth is one honest man to society and in the sight of God, than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.”[7]

The response from the American public was electric. Released to the general public in January, 1776, it sold 100,000 copies within three months of release, and went on to sell 500,000, this in a land inhabited by a mere 2,000,000 free men and women. (In all, 25% of the country read Paine’s argument for dissolving the relationship between the colonies and Great Britain.) Paine continued to publish pamphlets under the title, The American Crisis, thirteen in all, between 1777 and 1783. He was unrelenting, and his arguments continued to bolster the cause of independence from Great Britain by attacking the very foundations of the Anglo-American relationship.

On the topic of the shared ethnic heritage of American colonist to Englanders, he said:

“This new world hath been the asylum for the persecuted lovers of civil and religious liberty from every part of Europe…All Europeans meeting in America, or any other part of the globe, are countrymen. [But] not one third of the inhabitants [in America] are of English descent.” [9]

On the legitimacy of the English crown:

“No man in his senses can say that their claim under William the Conqueror is a very honorable one. A French bastard landing with an armed banditti, and establishing himself king of England against the consent of the natives, is in plain terms a very paltry rascally original. It certainly hath no divinity in it.”[10]

The point of even having a king:

“In absolute monarchies the whole weight of business, civil and military, lies on the king; the children of Israel in their request for a king, urged this plea ‘that he may judge us, and go out before us and fight our battles.’ But in countries where he is neither a judge nor a general, as in England, a man would be puzzled to know what is his business.”[11]

Never flagging, even in light of considerably negative reverses to the colonial cause throughout the war, Paine wrote in the darkest days of the war that:

“The people of America, by anticipating distress, had fortified their minds against every species you could inflict. They had resolved to abandon their homes, to resign them to destruction, and to seek new settlements rather than submit. Thus familiarized to misfortune, before it arrived, they bore their portion with the less regret: the justness of their cause was a continual source of consolation, and the hope of final victory, which never left them, served to lighten the load and sweeten the cup allotted them to drink.” [12]

In this last point, Paine was quite correct. War had been visited upon the colonies for close to five years. Scores of lives, property, fortunes and livelihoods had been put to flame for the cause of independence, and morale throughout the colonies–and the fighting forces—had been brought low. Paine would have none of it. If Paine was instrumental in mobilizing public opinion for fight for independence, he was similarly instrumental in mobilizing public opinion to continue the fight, no matter the costs.

The long war, begun in 1775 at Lexington and Concorde, concluded in 1782 with the American victory at Yorktown, Virginia. Great Britain formally gave up its ties to the American colonies in the Treaty of Paris in September of 1783, giving birth to the new American republic. The Churchillian phrase, “words are weapons in the wars of ideas”, could not have been more clearly exemplified than in this case. Paine is due no small credit for American independence through the weaponizing of his words. But he was not done.

Paine and the French Revolution

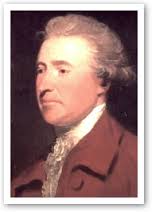

In the post-war period, Paine immersed himself in both inventing, drafting and selling a design for an iron bridge. (If viewed from the perspective that a bridge made of iron was but an extension of Enlightenment ideas, intent of remaking the old way of doing things, it seems a perfectly reasonable diversion.) In need of financial backing for his iron bridge, Paine journeyed to Europe, specifically France and England, in 1787. He struck up an easy friendship with Edmund Burke whilst in England, where they found common ground on myriad issues of the day. It would be a friendly acquaintance that would end acrimoniously three years later, after the seemingly progressive Burke published his acerbic, counter-revolutionary tract, Refections on the Revolution in France.

Consorting with republican, revolutionary types during his years in England (1787-1792) soon led to harassment by agents of the crown. It was in England that Paine started The Rights of Man, which argued for representative, republican governments throughout Europe. His agitations in England fueled his enemies within the British establishment. When informed of his imminent arrest, he took flight and crossed the English Channel. On landing in Calais, France, he was welcomed as a conquering hero. Clearly the French were familiar with his work.

One could say in this instance that lightning struck twice for Paine, in the sense that he found himself at the creation of not one, but two revolutions that shook the western world’s foundations. But unlike the American Revolution, which could in some ways be described as a relatively conservative one, the French Revolution very quickly became a revolution dedicated to destroying all vestiges of the past with a new, more democratic society, one based on equality, fraternity, liberty, and above all, reason. To Paine, the American Revolution didn’t go far enough in eliminating all traces of the desiccated past, and so he saw a second opportunity to influence the future in a more concrete way. Concurrently, the republican French saw an opportunity to recruit the author of Common Sense into their own movement, and made Paine an honorary Frenchman and a member of the new National Assembly. With his writings having found a large and enthusiastic audience in France, it was too good a public relations coup to pass up for all parties. That he had little facility with the French language wasn’t seen as an impediment.

Paine started writing The Rights Of Man in 1791 whilst still in England, and put the finishing touches on it in France. Composed of thirty-one articles, it was not only a spirited defense of the ideals of the French Revolution, but also went deep into the very essence of what society is and should be. Governance, religion, societal interactions: all topics were on the table for Paine. But if his philosophy could be pithily summed, it would be in this, “My motive and object in all my political works…have been to rescue man from tyranny and false systems and false principles of government, and enable him to be free and establish government for himself.” More succinctly put, “what matters most…is not..a sharp break from the patterns of the past, but that it is a replacement of wrong with right principles”. Pure consent of every citizen, or nothing at all, argued Paine. And as for those “false systems and false principles”, most everything fell into this category. Paine even went so far as to advocate for the scrapping of all laws and constitutions, in the sense that they were, as he saw it, the tyranny of the dead imposed on the living. “The vanity and presumption of governing beyond the grave is the most ridiculous and insolent of all tyrannies. Man has no property in man; neither has any generation a property in the generations which are to follow,” said he.[11]

But Paine’s involvement in the French Revolution soon turned into a dangerous situation for him. While in full alignment with its philosophical underpinnings, it did not shield him from its wrath. As the revolution developed a progressively radical—and murderous—tinge, Paine soon found himself labeled a counter-revolutionary. Indeed, he had allied himself with the Girondists, the more moderate faction of the nascent French Republic. Certainly, his arguments in the National Assembly–specifically that the King Louis XVI and Queen Mary Antoinette should be spared execution–won him no friends amongst the radical Jacobins, with a hostile Maximillian Robespierre at its head. He inevitably was arrested by the Jacobins in 1793, and was slated for execution by guillotine soon after. Only due to random luck did he escape losing his head under the “national razor”. His freedom was secured, after much negotiation, by Ambassador to France James Monroe, in November of 1794, who effectively argued that Paine’s American citizenship precluded him from French juris prudence. But feeling betrayed by the American government—he singled out then-President George Washington for particular opprobrium—for slow-walking (what he felt were) demands for his release, he remained embittered for the rest of his life. He was imprisoned for ten months; his health never truly recovered.

Paine stayed in France for several years thereafter, however. As a result of the Thermidor Revolt in July of 1794, which overthrew the Jacobin faction and put Robespierre and his junto under the guillotine’s blade, Paine was no longer in imminent danger. Perhaps due to the abrupt end to the Reign of Terror and the liquidation of the henchmen that ran the Committee of Public Safety (i.e. the leaders of the Jacobin party), Paine still maintained at least some faith that the French Revolution could be put to rights. Whilst still imprisoned, he started yet another group of articles that were to make up The Age of Reason. This time he had institutionalized religion in his sights: “The most detestable wickedness, the most horrible cruelties, and the greatest miseries that have afflicted the human race have had their origin in this thing called revelation, or revealed religion.”[12] He was just getting warmed up: “I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish Church, by the Roman Church, by the Greek Church, by the Turkish Church, by the Protestant Church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.”[13] Paine now staked out the deist ground, claiming that, “We have no idea of His wisdom but by knowing the order and manner in which it acts. The principles of science lead to this knowledge; for the Creator of man is the Creator of science, and it through that medium that man can see God, as it were, face to face.”[14] In perhaps what was the most important thought expressed in The Age of Reason, Paine wrote:

The inquisition of Spain does not proceed from the religion originally professed, but from this mule-animal, engendered between the church and the state…Persecution is not an original feature of any religion; but it is always the strongly-marked feature of all law-religions, or religions established by law. Take away the law-establishment, and every religion reassumes its original benignity. In America, a Catholic priest is a good citizen, a good character, and a good neighbour [sic]; an Episcopalian Minister is of the same description; and this proceeds, independently of the men, from there being no law establishment in America.[15]

Paine Returns To America

Thomas Paine stayed in France long enough to see Napoleon Bonaparte, the so-called “grave-digger of the revolution”, assume full dictatorial powers. It proved to be too much for Paine, and so in 1803, after a sixteen year odyssey that took him from America to England to France, he found himself back in America. This time, though, he was not a hero. His views on religion were not well-received, and while many (if not most) of what we now call the “founding fathers” of the United States might’ve been in synch with Paine’s deist, enlightenment views, the rank-and-file common man–i.e. Paine’s core readership–was not. However, he did still have friends in high places. Maintaining a friendship through correspondence with Thomas Jefferson, who was then president, he prevailed upon the president to make the Louisiana Purchase. While his influence in this endeavor was noted, Paine did not successfully dissuade Jefferson to prohibit African slavery west of the Mississippi. It was a tremendous blown opportunity for Jefferson, but it spoke well of Paine that he at least tried to dissuade Jefferson to settle those lands with “thrifty German settlers” and freed slaves. The roots of the American Civil War, it can be argued, began with this decision. Bleeding Kansas was a mere fifty years away.

Paine is said to have lived a barely subsistent life whilst late in life. His imprisonment in France during the time of the Reign of Terror left his health irreversibly damaged. With a reddened, splotchy visage, both critics and enemies would spread rumors that he had an addiction to strong waters, and would dismiss his anti-religious polemics as the rantings of a soft-brained drunk. He continued to write—of particular note was his pamphlet Agrarian Justice—but he was a shunned individual. That said, he held to his convictions until his dying day, having been said to have expelled two Presbyterian ministers who took it upon themselves to save his soul from damnation by scolding them that he’d have “none of [their] Popish stuff!”

He died on June 8th, 1809. He was buried on the grounds of his farm in New Rochelle, NY. Six people attended his funeral.

References

- [1] Hitchens, Christopher Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man, Grove Press, 2006

- [2] Ibid.

- [3] Thomas Paine“A Serious Thought”, Pennsylvania Journal, 18 October, 1775

- [4] Common Sense, Thomas Paine, Section II

- [5] Ibid.

- [6] Ibid.

- [7] Ibid.

- [8] Ibid.

- [9] Ibid.

- [10] Thomas Paine The American Crisis Section VIII

- [11] Thomas Paine, The Rights Of Man—Being an Answer to Mr. Burkes Attack on the French Revolution—Part 1 of 16

- [12] Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason

- [13] Ibid.

- [14] Ibid.

- [15] Ibid.