Lost In A Wilderness Of Mirrors

by Christopher J. Valentine

In a wilderness of mirrors…what will the spider do, suspend operations, will the weevil delay?–Gerontion, T.S. Eliot

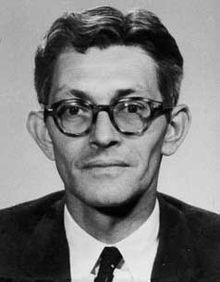

He’s been called “dominant counterintelligence figure in the non-communist world”[1] by former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) director Richard Helms, and a man who “saw a mole [i.e. double-agent] under every chair”, by Rolfe Kingsley, director of the Soviet Division of the CIA in the late 1960’s, who further described him as “a menace” [2]. He was said to have chain-smoked Virginia Slims, downed bourbon habitually, worked in a darkened, cigarette smoke-filled room surrounded by mountains of files. He had a habit of accusing those that disputed his conspiratorial theories as “one of them”, ostensibly inferring Soviet sympathies or worse. He obsessively cultivated orchids, as he felt that they showed “how deception works in the real world” [3]. He has been described as “brilliant”, yet alternately depicted as a paranoid, destructive conspiracy-monger. He was James Jesus Angleton. He studied poetry at Yale University, joined the Office of Strategic Services (OSS—the forerunner of the CIA) during WWII, then transitioned into the CIA thereafter. He would serve in the American intelligence services to 1975, when he was unceremoniously sacked by President Gerald Ford’s appointee as Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), William Colby. His reign as Chief of Counter-Intelligence (CI) is still strongly discussed, his legacy still hotly debated. (He was CI for twenty years between 1955 to 1975.) But more than that, Angleton played a central role in one of the most damaging and confusing events to ever grip the American intelligence apparatus. It is the story of two Soviet defectors, both of whom gave conflicting and contradicting information to the CIA, and who forced every major player in the CIA and the FBI to take sides as to which of the two was real, and which one was the agent provocateur. It has been called “the war of the defectors”–an apt description. This is the story of Yuri Nosenko, Anatoliy Golitsyn, and James Angleton. It is the story of a game where every player lost, and no player won.

A Spy Comes In From The Cold

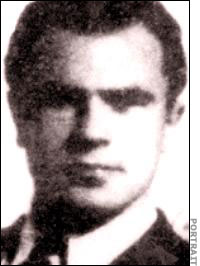

December 15, 1961, Helsinki, Finland: A man in a heavy overcoat walks into the American embassy and asks for the CIA station chief, Frank Friberg. The fact that someone could walk off the street in a snowstorm and ask for Frank Friberg—that he even knows who he is–stuns the staff at the American embassy from the start. His name is Anatoliy Golitsyn, a consul at the Soviet embassy. Friberg meets with him immediately, and in that first meeting on that snowy day, Golitsyn hands over a pile of classified documents lifted from the Soviet embassy. More to come, he says. Friberg asks him if he could stay where he is within the Soviet embassy, as an “asset in place”—act as a double-agent and filter important info back, but without defecting. An impossibility, says Golitsyn. He has to defect by December 25th, as he is scheduled for reassignment back to Moscow. He insists that his wife and daughter be allowed to defect with him. Additionally, he says that the KGB has ways of finding out who’s feeding the CIA classified info, and that he will be found out and executed thereafter…in fact, he is already vulnerable. Nothing short of asylum is an option.

Friberg thinks this an astounding development, not just because Golitsyn volunteers highly-classified information unprompted, but also due to the revelation that the CIA has been so infiltrated by the KGB that an individual like Golitsyn can be found out to be a double-agent. Getting wind of this, the brass back at CIA headquarters frantically search out Golitsyn’s background. The files on him are skint, but an earlier KGB defector in 1954 mentioned Golitsyn as a possible recruit for the CIA as an “asset”—one within the Soviet apparatus capable of filtering secrets to the Americans. His bona fides tentatively established, Golitsyn and his family board a military personnel plane and head to West Germany on December 25th,, 1961.

Back in Frankfurt, West Germany, Golitsyn writes out his entire C.V. with the KGB from the beginning of his career to present-day. He is given numerous lie-detector tests. He is interrogated for days on end. His answers stand up well, matching up with information the CIA interrogators already know to be true, whilst providing additional information to fill in blank spaces. “By the end of the first week, the CIA [is] fully persuaded that he [is] a bona fide defector who has indeed held the positions in the KGB he claimed” [3] On arrival to the States, Golitsyn is further debriefed, and provides extraordinary information regarding the KGB’s penetration of western intelligence agencies:

To the amazement of his debriefers, he not only revealed knowledge of a wide range of secret NATO documents — but he identified them by their code numbers. He explained that for convenience the KGB used the NATO numbering system to request specific documents, which would than arrive from its source in France in 72 hours.[3]

The Golitsyn defection reaches the level of President Kennedy, who makes an unfortunate call to Charles de Gaulle, president of France, to tell him that according to Golitsyn, French intelligence has been compromised and infiltrated at the highest levels by the KGB. The French send their own intelligence agents to interrogate Golitsyn, and come away shocked: Golitsyn tells them about top secret data that only those at the highest echelons of the French government could’ve possibly known.

Golitsyn is the real thing, determines CI James Angleton, who bestows his benediction—bona fide–on the Soviet defector. One more thing, says Golitsyn…the KGB will send over another defector to discredit me, to muddy-up the veracity of my information. It will happen soon. Caveat.

A Drunk Get Rolled In Geneva

June 8th, 1962: A man attached to a Soviet delegation arrives in Geneva, Switzerland for an eighteen-nation conference to discuss disarmament. On his first night in Geneva, he manages to get himself extremely inebriated on vodka, then proceeds to get rolled for $900 ($200 in US dollars) in Swiss francs by a prostitute. He is a KGB man, having managed entry to the organization, despite his taste for vodka and disreputable women, due to his family connections. (His late father was a confidante of Soviet Premier of Nikita Khruschev, and so many looked the other way at the young man’s proclivities.) Fearing severe retribution by his superiors for having lost money in such a careless way—the KGB did not look kindly on their agents getting rolled by ladies of the night, or by anyone else for that matter—the man approaches a member of the American delegation at the conference. “I’d like to talk to you, but not here,” he says. He proposes lunch with the American. They meet at a restaurant a day or two thereafter. The Russian pitches the American diplomat: I’ll provide you classified information, but I need money, lest my superiors find out about my escapade. The American diplomat cautions the Russian that he’s about to commit treason. It matters not to the Russian; let’s meet again, and I’ll have some valuable information for you. They decide on a meeting the next day at a less conspicuous location. The American diplomat notifies Washington of this development.

Two CIA interrogators are rushed to Geneva for the meeting with the KGB man: Tennent “Pete” Bagley, a member of the Soviet Division at the CIA, comes in from nearby Bern, Switzerland; George Kisevalter, considered to be the primary spy-handler in the CIA, comes in from headquarters. The KGB man is Yuri Nosenko…and he arrives drunk as a skunk to the meeting. They have a few more meetings at various safe-houses. Nosenko comes through with the information he promised his CIA handlers. He answers in the negative when asked if he wished to defect; he has a wife and kids in Russia. Pete Bagley, euphoric that a genuine “asset in place” has been successfully recruited, cables HQ and says that Nosenko is the real thing, his bona fides proven. The CIA will have a genuine mole in the KGB—a serious win.

The case file winds up on the desk of James Angleton. Angleton’s job is similar to a fact-checker at a newspaper or an internal investigations officer in a police department, only his responsibilities are to see that agents in the field don’t get gulled by their Soviet counterparts, or that one of them doesn’t wind up becoming a KGB asset—a turncoat. Bagley isn’t a direct subordinate of Angleton’s, but thinking it a smart political move to keep Angleton in the loop, he consults him; Angleton is entirely too powerful within the agency to ignore. Arriving at HQ, Angleton hands Bagley a file to read. He is told the file is so highly classified that it cannot leave the office. Bagley gets down to reading it…and is horrified. The information he received from Nosenko isn’t fresh or new, but in fact terribly suspicious:

Each point in Nosenko’s story paralleled information given by the earlier defector. When the two stories were compared, it became clear that Nosenko was a “provocation”, sent to Bagley in Geneva by the KGB to supply clues that would divert from and confuse the intelligence the CIA already had from the real defector. Bagley understood, even before Angleton told him, that he had been duped by Nosenko. [4]

For his part, Angleton isn’t terribly surprised or concerned. In fact, he views these developments as somewhat of a positive. He tells Bagley that the information he just read was supplied to the CIA by a defector—he refers to him as “Mr. X”—who came over in December of 1961 through the US embassy in Helsinki. Angleton’s conclusion is that Nosenko is clearly a “controlled source”, meaning he was still being controlled by the KGB. He is there to spread disinformation, to damage Mr. X’s credibility. Why not turn the tables and feed him disinformation, essentially deceiving the deceivers? Bagley soon returns to Geneva. He doesn’t hear back from Nosenko after returning from Washington.

The Golitsyn Prophecy Fulfilled

President John F. Kennedy is assassinated in Dallas, November 22, 1963. All levels of the US government are on high alert. Lee Harvey Oswald emerges as the assassin. He is an avowed communist, known for distributing leaflets published by the “Fair Play For Cuba Committee” on street corners in New Orleans. (Oswald is the only member of the aforementioned committee.) He is married to a Russian woman, having met and married her during his time in Moscow a few years earlier. He is a former Marine, trained in aircraft surveillance and radar, stationed at a naval airbase in Atsugi, Japan. His resume is terribly suspicious. Questions immediately arise. Was he alone in this? Was he a KGB assassin? A sitting president killed by an avowed communist who spent three years in the USSR, then re-emigrates back to the US…very suspicious, indeed. Yuri Nosenko surfaces and makes contact with the CIA six weeks after the Kennedy assassination. He wants to meet Bagley when he is back in Geneva the next week. On January 23rd, 1964, he meets Bagley at a safe house, pours himself a drink, and declares that he is ready to defect. Bagley knows that Nosenko is utterly useless as a defector, particularly if he is still controlled by KGB, which is the consensus opinion at the CIA. But then Nosenko drops an even bigger bombshell: he has information about Lee Harvey Oswald. He goes on to explain that he has seen the KGB file on Oswald; after all, he was Oswald’s case officer. But he has to defect before February 4th, when he’s scheduled to return to Moscow. He fears he’ll be arrested. Given the circumstances, the CIA had no choice but to sneak Nosenko out. The Kennedy assassination is too fresh, so many questions yet unanswered; to risk letting a KGB agent go who says he has critical information about Oswald’s time in the USSR would destroy careers at the CIA.

After a stopover in Frankfurt to debrief, Nosenko arrives in Washington on February 11th, 1964. Nosenko is now a defector. More debriefs. He’s now in a CIA safe house. A few things are determined: a.) If Oswald had made contact with the KGB during his time in the Soviet Union, he would’ve been handled by the KGB’s Second Chief Directorate Tourist Department, b.) Yuri Nosenko was a part of the Second Chief Directorate, c.) One of the Second Chief Directorate’s duties is “wet work”, i.e. assassinations. As for Nosenko, his information on Oswald is rather flat and anti-climactic. Oswald was mentally unstable, he says, and we had no use for him; we suggested he go home to the United States. And that was that.

James Angleton thinks this patently false. Nosenko, it seems, has been caught out in several untruths already, among them: he exaggerated his rank within the KGB (he said he is a colonel, when in fact he is a captain), and more importantly, the National Security Agency (NSA)—charged with monitoring Soviet communications—finds no evidence that any cable arrived from Moscow stating Nosenko was to return. There was no recall order. Additionally, if Oswald was based at Atsagi Naval Air Base, was an aviation electronics specialist, he must’ve had some value to the Soviets, no? His story doesn’t make sense. Angleton decrees that Nosenko is lying.

Three Years In Hell

Nosenko floods his CIA handlers with a torrent of secrets. It is not enough, and not what they’re looking for. He is not coughing up the critical data, specifically regarding the Kennedy assassination, nor his true role in all of this. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, the brother of the slain president, approves the consignment of Yuri Nosenko to solitary confinement. He is subjected to sleep deprivation, lousy food, no human contact, very little light, and no time outdoors. He is worked over psychologically and physically, specifically by Ted Bagley, his initial CIA handler in Geneva. CIA Chief Richard Helms notifies Chief Justice Earl Warren, the man in charge of investigating the Kennedy assassination, that the CIA has Nosenko in custody. Despite Nosenko’s connection to Oswald, his name is omitted from the Warren Report. And all the while, through it all, Nosenko sticks to his stories. He never breaks–despite the interrogations and ill-treatments–for three years.

Concurrently, deep schisms develop within the intelligence apparatus of the United States. The FBI is now involved, as Director J. Edgar Hoover sees Nosenko as a bona fide defector. Hoover pokes his nose in to the CIA’s business due to the fact that he has two KGB moles of his own, codenamed Fedora and Top Hat, who have been providing the FBI with secrets while maintaining positions within the Soviet delegation to the United Nations in New York City since 1962. The diplomatic positions are a cover; they’re both KGB operatives. Both of these moles are ostensibly acting separately from each other. Their stories match up with the information that Nosenko has provided, almost verbatim. The ultimate arbiter, Angleton, thinks they are “dangles”: KGB agents sent to provide bogus information to the Americans, to throw more mud into the already opaque waters. Careers begin to get damaged: William C. Sullivan, FBI man in charge of counter-intelligence, runs afoul of Hoover by claiming that Fedora and Top Hat are double-agents, and by extension, Nosenko. Sullivan’s opinion implies that Hoover has been duped. Sullivan soon becomes persona non grata at the FBI. Angleton maintains that Nosenko is bogus, and worse, part of a conspiracy to derail any leads that follow back to the KGB with regards to the murder of President Kennedy. But with the pressure to get Nosenko to confess comes increased pressure from forces outside the CIA—Hoover at FBI, members within the American political sphere privy to his existence—to release him from his indefinite detention. By 1967, unable to coax a confession out of him, the CIA has no choice but to release him.

Who Was Real?

Anatoliy Golitysn’s bona fides are never doubted by Angleton, who is the only man with whom such things truly matters at CIA. But there are those who have their doubts. Despite Golitsyn’s initial debriefs, rich with good, high-level information, he subsequently feeds Angleton strange theories. Angleton, with a unshakeable belief in Golitsyn’s value, acts on these theories, none of which yield anything of value. Golitsyn tells Angleton that there’s a mole within the CIA with a Slavic last name that starts with the letter K. An agent by the name of Peter Karlow pays dearly for this, losing his position at the CIA in 1963; he eventually is cleared of all wrongdoing in 1988, twenty five years after his name is sullied. Golitsyn feeds him some more strange theoreticals: One claims the rift between the Red Chinese and the Soviets in 1961 (the Sino-Soviet split) is a ruse to fool the West, with its intent on splintering solidarity amongst the western powers; better to pick them off one by one, as Golitsyn tells Angleton, who runs with it. (DI Richard Helms dismisses this as nonsense.) Golitsyn also feeds Angleton the theory that British Prime Minister Harold Wilson is a Soviet mole; MI5, the British equivalent of the FBI, finds nothing. He accuses Canadian Prime Ministers Lester Pearson and Pierre Trudeau of similar activities. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) find nothing on either man. The Canadian Ambassador to the USSR, John Watkins, is not so lucky: he dies during interrogations by the CIA and the RCMP. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger is also accused of being a Soviet mole by Angleton; Kissinger’s responds accurately by stating that no matter how brilliant and loyal Angleton may be, there’s no way he could stay in counter-intelligence for so long without going mad with paranoia. But Angleton’s faith in Golitsyn–the source of these theories–remains unshakeable. Important intelligence from other sources gets thrown in the bin, much to the resentment of others in the agency, who worked so hard to obtain it. Angleton runs all data past Golitsyn, who usually sits in negative judgment of these offerings.As a result, Angleton becomes the most hated and feared man in the CIA by those within the organization. Golitsyn’s reputation plummets along with Angleton’s.

Freed in 1967 with an apology and a consulting job with the CIA, Nosenko’s reputation concurrently rises as the Golitsyn’s and Angleton’s reputations decline. Angleton staves off all attempts at removal as CI by coming up with a critical and timely piece of intelligence: weeks in advance of its occurance, he accurately reports that Jordan, Egypt, and Syria are mobilizing to attack Israel. The event comes to be known as the Six Day War. Even President Johnson is impressed by this intelligence coup. Angleton remains secure until late 1974, despite his tattered reputation. Golitsyn, by extension of having Angleton’s ear, continues to feed Angleton questionable intelligence.

In The End…

Inevitably, no one to this day is fully sure who the real defector was. Angleton gets fired by Richard Helms’ replacement, William Colby, under direction of President Gerald Ford. (Angleton suspects Ford of being a Soviet spy as well.) Golitsyn inevitably gets dismissed as a crackpot. One source in MI6, the British equivalent of the CIA, claims that Golitsyn was a genuine defector that simply ran out of bona fide intelligence and lapsed into fantasy to keep himself relevant. Yuri Nosenko is subsequently credited for the following:

[Nosenko] has identified, or produced investigative leads on, some 200 foreigners and 238 Americans in whom the KGB had displayed interest. He has fingered some 300 Soviet intelligence agents and overseas contacts, and roughly 2000 KGB officers. He has pinpointed fifty-two hidden microphones that the Soviets had placed in the American embassy in Moscow. He has expanded the CIA’s knowledge of how the Soviets sought to blackmail foreign diplomats and journalists.[6]

To put it into further perspective, one writer on the subject stated that one must take on faith that “Moscow would trade all that information to protect one mole” [7].

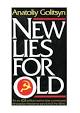

As for Angleton, he still has his defenders, who point to the fact that during his twenty year tenure, the CIA had no high-level moles within the agency. Aldrich Ames, considered to be the most damaging double-agent in agency history, begins feeding critical information to the Soviets a full ten years after Angleton resigns as Director of Counter-Intelligence. Angletonians claim an agent such as Ames would’ve never have gone undetected if Angleton were still CI. As for Golitsyn, he goes on to write books such as The Perestroika Deception, which claims that the Soviet initiatives undertaken during the tenure of General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev were a ruse to lull the West into a sense of false security. In another of his books, New Lies For Old, Golitsyn postulates that the Soviet Union will fake its collapse, with the express purpose of gulling the West, only to reconstitute itself with leadership derived from the KGB. (His prediction that the USSR would collapse was made in 1984, some seven years before it did so.) Given the current state of Russia, with former KGB operative Vladimir Putin at the helm, Golitsyn might have been onto something. As for the two KGB moles who corroborated Nosenko’s resume and information, Fedora and Top Hat, the consensus thinking is that Fedora was in fact a double-agent. On the other hand, Top Hat, later identified as Dmitri Polyakov, turned out to be a genuine CIA asset within the KGB. He is identified as such by turncoat Aldrich Ames, and executed by the Soviets in 1988.

Yuri Nosenko dies in 2008. James Angleton goes to his grave (he passes in 1987) believing that Nosenko is bogus. Ted Bagley, his initial handler back in the early 60’s, writes in 2007 that Nosenko was a “provocateur and a deceiver”. For his part, Angleton claims he saw no need to keep Nosenko in detention for the better part of three years; that was the decision of others in the CIA Soviet Division. But there can be little doubt that it was Angleton’s “not bona fide” malediction that consigned Nosenko to his hellish detention.

In 1975, Nosenko looks up Angleton in the Virginia phone directory. Strangely, he is listed. He calls and gets Angleton on the phone. Perhaps looking to square the circle, Nosenko queries Angleton as to why he was treated the way that he was. Angleton answers that he had nothing to do with his detention and treatment thereafter, but he still feels that he is a fraudulent defector. “I have nothing more to say to you,” says Angleton. Nosenko responds in kind, and hangs up the phone. Nothing get settled. It still hasn’t, almost fifty years later.

The postscript on the Nosenko affair is best summed up by the obituary written in The Economist for Yuri Nosenko in 2008, “America’s spies were as thoroughly divided about him as any KGB agent could have wished.”[8] If Nosenko was indeed an agent provocateur, he succeeded beyond all expectations. One might say the same for Anatoliy Golitsyn. As for Pete Bagley, he wrote extensively about the Nosenko affair in his book, Spy Wars, published in 2007. He was scheduled to give a talk on the book at the International Spy Museum in Washington, DC to coincide with its release. But at the last moment, he was abruptly cancelled by museum director Peter Earnest. Bagley bitterly complained that it was, “because the old spies that run the place back the official CIA position that Nosenko . . . was legit, not a provocateur.” For his part, Earnest states on the record that he has heard from old CIA alumni “whose careers were ruined” by the whole affair. As Earnest puts it, “interestingly, forty years later, feelings are [still] very sharp.”

- [1] Richard Helms, A Look over My Shoulder: A Life in the Central Intelligence Agency (Random House, 2003) pg.27

- [2] Ron Kessler, The CIA at War: Inside the Secret Campaign Against Terror, (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2004) pg. 56

- [3] Edward J. Epstein, Deception: The Invisible War Between the CIA and the KGB, (Simon & Schuster) pg. 57

- [4] Edward J. Epstein, Through The Looking Glass, article. http://www.edwardjayepstein.com/archived/looking.htm

- [5] Edward J. Epstein, Deception—The Invisible War Between the KGB and the CIA, (Simon & Schuster) pg. 16.

- [6] Tim Weiner, Legacy of Ashes—The History of the CIA, (Anchor Books, 2008) pg. 270

- [7] Ibid.

- [8] The Economist, Yuri Nosenko Obituary http://www.economist.com/node/12051491

- Also consulted: David Wise, Molehunt: The Secret Search for Traitors That Shattered the CIA, (Random House, 1992)